Coronavirus: The Basic Dance Steps Everybody Can Follow

Over 10 translations available at the bottom of the article. More translations welcome.

My two previous articles, Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now and The Hammer and the Dance, have gathered over 60 million views together and have been translated into over 30 languages each. This installment is Part 2 of a series (part 1, part 3, part 5) that focuses on the specific steps required to open up the economy. To receive the next ones, sign up here.

Summary: Any country can follow a series of measures that are very cheap and can dramatically reduce the epidemic: mandate wearing home-made masks, apply physical distancing and hygiene everywhere, and educate the public.

In Part 1, we showed the paths that different East Asian countries followed during their dance against the coronavirus. Some patterns started to emerge about the measures that matter most.

It’s time to dive deep into all these possible measures, to understand them really well and decide which ones we should follow. We can split them into 4 blocks:

- Cheap measures that might be enough to suppress the coronavirus, such as masks, physical distancing, testing, contact tracing, quarantines, isolations, and others

- Somewhat expensive measures that might be necessary in some cases, such as travel bans and limits on social gatherings

- Expensive measures that might not always be necessary during the dance, such as blanket school and business closures

- Medical capacity

During the Dance, when we relax the lockdown and start going back to normal, the goal is to combine measures that get as much economic activity back to normal, while keeping the virus’ transmission rate below 1 — so that it doesn’t spread widely — until either a cure or a vaccine is discovered.

Today we’re going to focus on the very cheap and easy measures that anybody can apply, and the massive impact they can have. Let’s start with the most obvious of them all: Masks

Masks

As we saw in the first article, masks are widely used in East Asia: China, South Korea and Taiwan, but also Hong Kong and now Singapore. But these are not the only countries that trust masks. As of April 22nd, 2020, 51 countries mandate them in some public activities, including countries such as Germany or Taiwan. That’s over 25% of all countries:

This is for mandates. But many more countries recommend masks, including all of the G7 (except for Italy and the UK). In the US, a number of cities, including New York, Austin, Los Angeles, and San Francisco have passed mandates over the last few days.

But until very recently, we were told not to wear masks. As of April 22nd, the WHO still recommends not to wear a mask if you are healthy. And most countries still don’t mandate them in public. Why? Who is right?

To know the answer, we need to understand the science behind how the coronavirus spreads.

The Science of How the Coronavirus Spreads

Respiratory infections use your mouth and nose to spread through three mechanisms:

- “Droplets”: drops of liquid that you eject from your mouth and respiratory tract

- “Aerosols”: very small particles that mix with the air and can remain there for hours

- Surfaces: for example, you cough on your hand and use a door knob that somebody else touches afterwards

For the coronavirus, many scientists initially thought that most contagion happened through droplets when people coughed, and that these droplets fell quickly to the ground, within a few seconds of the cough and no farther than 2 meters (6 feet). If that had been true, it would have meant that the main way you got infected was if somebody coughed in your face, or if you touched a contaminated surface.

Since usually nobody coughs in your face, authorities argued that the value of wearing a mask was low for average people. But for healthcare professionals, it was huge, because they get these droplets on the face all the time from patients that are sick and cough in front of them, when they intubate them, or in similar situations.

Since there were very few masks available, several authorities around the world decided to prioritize them for healthcare workers, and recommend against their use to the rest of the population.

It was the right thing to prioritize healthcare workers, but instead of saying: “They’re much more useful to healthcare workers, so the right thing is to keep masks for them” they claimed that they were useless—or even dangerous—for the general public. That undermined the credibility of authorities.

Then this evidence started coming.

Apparently, in coughs or sneezes, droplets could be carried away much farther than 2 meters (~6ft), and they didn’t fall so fast to the ground. Some did, but many remained in a cloud of droplets.

Then, it was discovered that you don’t even need to cough. Singing could be enough. In a 60-people choir in Washington State, 45 members got infected. Even talking is enough:

Or just breathing!

That makes masks very very important. A mask can stop infected people from emitting droplets, and healthy people from receiving them.

But there are no masks! There’s a global shortage of them. The few we have should be for healthcare workers. What do we do?

Thankfully, some researchers have discovered that you don’t need professional masks. Home-made masks are also quite good.

This impressive paper (preprint) reviews all the evidence around whether masks work or not. The main conclusion is that they work. Wearing them can have a tremendous impact on reducing the transmission rate.

This is true to protect people who are healthy, but especially true for infected people: Wearing a mask traps most droplets and also prevents them from forming a cloud that remains in the air, as we saw in this video.

You could say: “Perfect! As soon as somebody is sick, they should wear a mask.” That is unfortunately too late.

A great paper from Oxford University published in Science goes through great lengths to identify how the coronavirus spreads from person to person. The horizontal axis shows days since the first infection, and the vertical axis shows how many other people are infected in different ways on any given day. For example, on Day 5 after contagion, carriers infect on average close to 0.4 other people. Most of that comes directly from people who are already symptomatic or who will soon become so (so they’re called pre-symptomatic). A little bit of it is through the environment (probably surfaces), and even less comes from people who have the virus but will never develop symptoms.

What this really shows you is that broadly half of infections come from people who have symptoms, but half come from people who don’t have them yet. If only people with symptoms wear masks, you will prevent less than half the infections. If everybody wears them, you could prevent most of them.

Everybody should wear a home-made mask: You can infect other people before you know you’re sick.

How much can we reduce R through masks? Quite a lot.

According to this model, just 60% of people wearing masks that are 60% effective could, by itself, stop the epidemic.

This doesn’t even include another value of masks: preventing infectious people from contaminating surfaces, and healthy people from touching them and carrying the virus to their face.

I don’t know you, but I can’t help myself. I touch my face all the time. Having a mask on stops me from touching my face, which likely reduces contamination through surfaces by stopping my dirty hands from touching my eyes, my nose or my mouth.

So you should wear a mask. But you can’t wear surgical or N95 masks yet because in most countries there are not enough of them, and the few we have should be kept for health workers. You need to make one for yourself. What should you make it with?

There are four factors you should consider:

- The material

- The density

- The number of layers

- The Combination of layers

On (1) the materials:

Some fabrics are better than others, but many are great.

The fabric should be chosen to be as dense as possible. For cotton masks, we should use the highest thread count we can. As a rule of thumb, the less a fabric lets light go through, the better. You also want to be able to breathe, however.

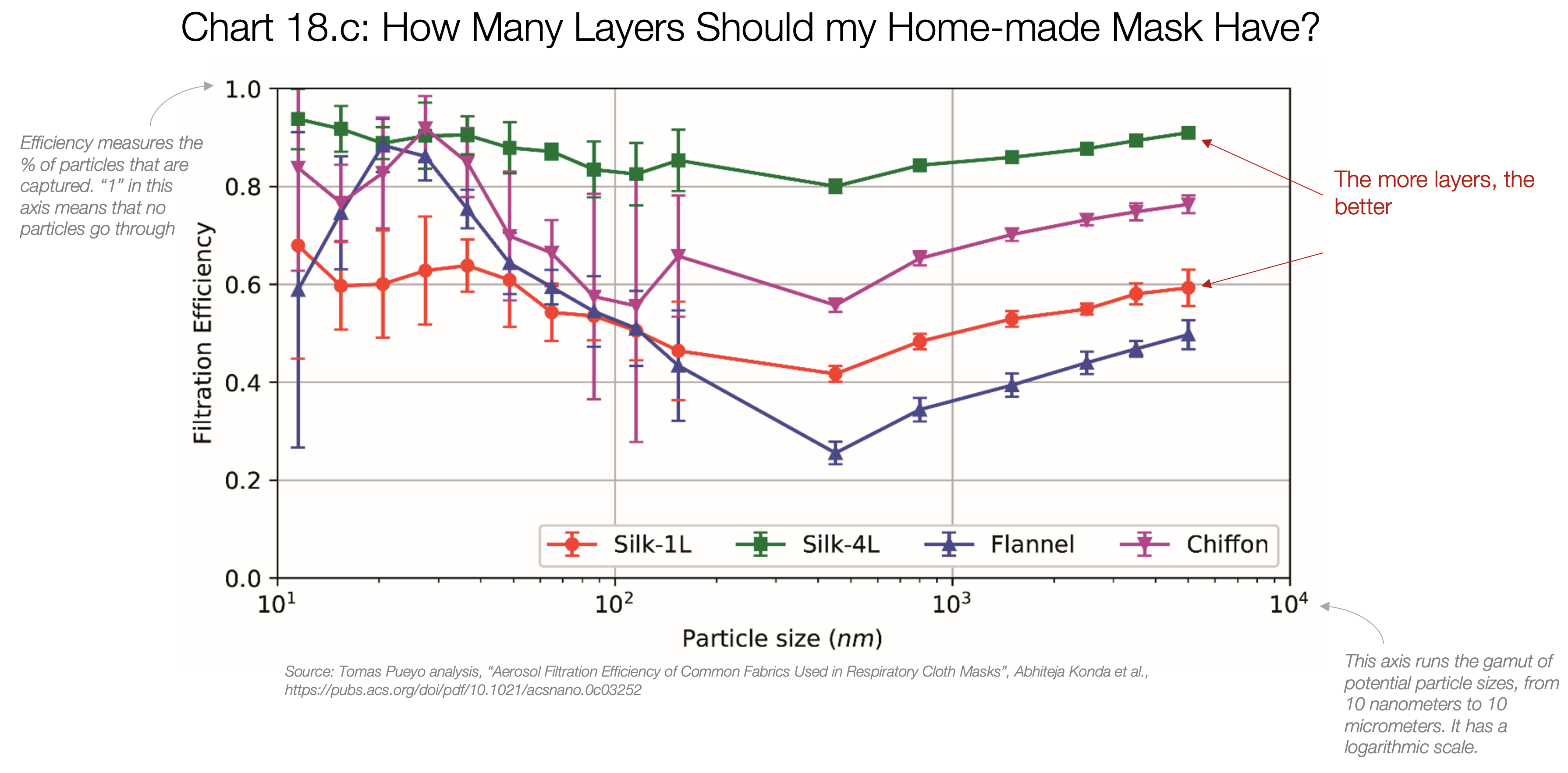

How many layers should it have? The more, the better.

Finally, should you combine materials?

All of this suggests that you should pick materials that are denser, combine them with different materials, and have as many layers as you can to breathe. But be careful: If you can’t breathe easily, you will take it off or have air go around the mask. That’s bad. Make sure the fit is good. Otherwise, the efficiency of the mask will plummet.

Ready to make your mask? Here’s a way to do one in 40 seconds, or a more comprehensive one.

If you do wear a mask, it’s also important to learn how to put it on and off to avoid cross-contamination.

Since everybody has an old t-shirt at home, homemade masks cost nothing — governments could even make money out of them by fining those who don’t wear them. And yet every single one of them can produce between $3,000 and $6,000 of value in reduced mortality. That’s an infinite return on investment.

With this type of impact, cost, and ease of implementation, masks are a no-brainer. Even if the confidence in their impact was low, it would still be a no-brainer given the cost. Japan didn’t take too many measures against the virus and yet it has a much lower transmission rate, with heavy mask-wearing by the public. Czechia and Slovakia, the first countries to mandate masks in public in Europe, have some of the best case trajectories in Europe.

Governments across the world should make mask-wearing mandatory in public. There should be penalties for not wearing them. Companies should demand it from their employees. Shops should demand it from their customers. We need to change as a society and not see masks as the mark of somebody sick, but as a mark of somebody intelligent and considerate of the rest of society.

And if governments don’t do it, citizens should. After all, if Czechia went from 0% to 100% mask-wearing in public in 3 days, so can you.

In summary, what have we learned about masks?

- The coronavirus can spread not just through coughs within 2 meters, but even through singing or talking, and maybe much farther than 2 meters

- Most people are infectious before they even know they’re sick

- Wearing masks prevents sick people from infecting others by keeping their droplets inside the mask

- They also protect healthy people from being infected

- You can have 100% of your population wear house-made masks within a matter of a few days

- If a majority of people wear house-made masks that are reasonably effective, that measure alone could stop the epidemic

- It’s one of the cheapest things any country — or person — can do

- Given the cost (nothing) and the benefit (huge), mandating them is a no-brainer.

This section draws heavily on ideas and sources from Jeremy Howard, Masks4All, and Matt Bell’s deep dive on masks.

Physical Distancing, Hygiene, and Public Education

Now that we know that the virus spreads through cough, droplet clouds, surfaces, or even speaking, we know to wear masks. However, not everybody might wear them, or they might not be perfect. We can limit contagions in other ways too, simply by changing our day-to-day behavior and our environment.

Since most infections happen through other people, whether symptomatic, pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic, what we want is to avoid prolonged, direct, confined contact with people if it’s in a closed area, and we have close contact for a long period of time. In such an environment, two meters is likely not enough space. This paper explains why.

It shows the physical position of different coronavirus patients that were at a restaurant at the same time in China. They belonged to three different families, but were connected through contact tracing.

Here, A1 was the first one to show symptoms, later the same day. That patient might have been the only one infected in the restaurant, or maybe A2, A3 and A4 might have been too since they developed symptoms 2–3 days later. Later, five other people from two different tables also got infected.

The people infected from other tables were either close to the infected — who could have infected them through droplets — or in this patient’s visual field a few meters away. The contagion there could have been through contact or a droplet cloud, who knows. It was, however, most likely from A1—since that patient was closest to symptom onset—but might also have been from other members of the household, although less likely since their symptoms were still 2–3 days out. Family A overlapped for over 1 hour with both families B and C.

It looks like this is one of the key things to avoid: prolonged, closed contact in a confined environment. How can we apply that learning?

First, we need to separate tables in restaurants and maintain distance between people. There should be at least 2 meters between people—if possible, more—and we should avoid having a lot of talking for a long time.

This video shows how environments have been adapted in China. For example, a restaurant uses half the tables as a buffer and doesn’t allow people to sit together to eat, or for people to sit in front of one another.

Taxis are another example of confined area where contact can be prolonged. Masks and disinfecting are an obvious necessity, but it might not be enough. We might want to split the passengers from the cab drivers.

Gyms are another example. These guys marked areas on the floor to make sure people remain far from each other during their workout, and have everything they need to disinfect their area. This distance might not be enough, but it gives a sense of what might work.

Whenever possible, physical barriers should be erected to separate people. This Starbucks in Taiwan marks the floor to make it clear where people should stand.

The image comes from an illustrative video of what life feels like in Taiwan right now, including masks, thermometers, schools, sanitizer in elevators, hand-washing stations, and other measures.

All physical work settings should have similar measures: separate people as much as possible, create physical barriers if possible, have good air movement, and avoid prolonged contact between workers.

For people working in the office, the same types of rules apply:

- Mandate masks.

- Those who can work from home, should. Especially those who need to take public transit, or those who are in a vulnerable group, such as older people or those with co-morbidities.

- There should be hand sanitizer everywhere, and the office should be cleaned very frequently.

- Avoid physical meetings. If they need to happen, avoid too many people in the room staying close to one another for too long. Ten-person meetings that last an hour are not a good idea. Whiteboarding with co-workers for long periods of time might not be a great idea either.

- Don’t work face-to-face

- Structure entries so that crowds become impossible

- Have hand sanitizer in elevators, or tissues and a trash can so people can press the button with it instead of their hands

- Create physical barriers where needed. If people might be tempted to lean on them, try to make it so it’s inconvenient, and have signage that forbids it.

- Whenever possible, create different shifts and split workers across them.

- Canteens should move to takeaway. Eating time should be extended so that people don’t crowd in the same area.

- Try to avoid mixing different networks inside the company. Teams that always work together and don’t hang out with others be less likely to be infected from other networks that have carriers.

- Obviously, anybody with symptoms should immediately leave and get tested, and all contacts should be monitored or quarantined.

- For that, it might help to keep track of all work-related contacts. One way of doing that is to mark every interaction with people on the calendar.

- For other types of working environments, such as logistics, in-home, or outdoors, here are some other recommendations.

There are many documents suggesting measures like these. This is the one from the US’s CDC, and from the UK government.

Besides work, social life is another source of contagion. As we saw before, prolonged contact while talking, singing, or having physical contact should be avoided.

Unless you live in the same household, avoid hugging, kissing, shaking hands, or sharing food. Avoid organizing parties or social gatherings, including birthdays, weddings or funerals. They might kill people, like this man from Chicago who infected 16 other people in a funeral and 3 of them died.

These measures will limit our infections directly from other people. This is the highest priority.

But we can also be infected through the environment.

It’s unlikely that you can get infected by viruses that land on your hair, clothes, or even mail packages: They don’t tend to land there, and when they do, they likely don’t survive too long. If you are not with other people, contagions outdoors are also unlikely, especially under sunlight.

What can happen, however, is to get infected through your hands, by touching a contaminated surface. This is why it’s crucial not to touch your face, but also to wash your hands.

Both washing hands and disinfecting them with sanitizer work, but properly washing hands is considered better.

This is how soap works to kill the virus:

Viruses have a fatty surface, so soap sticks to it like it does to normal fat when you clean your dishes.

This quick video illustrates how to wash your hands well, and why:

All of these measures can reduce the spread of the coronavirus. We don’t know which ones contribute how much, and we may never know. But this is our best guess based on what we know about the virus.

As a result, citizens, businesses and governments should be pushing these measures through education campaigns and enforcement measures.

On the education side, for example, many governments send text messages to all the population several times a day. Through these and other national broadcasting media, they can communicate these core messages over and over again.

For an added level of adoption, they can have fines for those who visibly don’t respect them. This is what happens in Taiwan, for example.

Since normal businesses must adapt their workplaces and mandate telework as much as possible, this is even more true in the healthcare system. It deserves a small section.

Healthcare workers are both crucial fighters against the virus and most at risk to be infected. Many measures can help reduce the risk, but the best measure is to not have contact at all. That means taking as many consultations as possible remotely.

Aside from reducing contagions in the hospital, telemedicine also reduces the load in hospitals and waiting rooms. It’s also a way to recruit people’s time at home to take care of themselves. They are sent home with pulse oximeters or digital stethoscopes, so they can check their evolution and go to isolation if symptoms appear. It’s also a great way to triage people upfront, in the cases when they believe they might be sick but their symptoms don’t match those of the coronavirus’.

Some countries like the US already have a great legal framework for telemedicine. Others, like the EU, will have a harder time. But given the circumstances, it’s worth revising it.

Temperature Checks?

The last measure that we’ll cover today is temperature checks.

First, temperature checks will only work for people who already have symptoms — which, as we now know, cause only about half of transmissions. Out of them, not all have a fever. Temperature checks will catch less than ~50% of infected people.

Yet China and Taiwan, among other countries, test for people’s temperature at the entrance of many places. Those thermometers don’t touch the skin, to avoid surface contamination. Unfortunately, the average one doesn’t work that well. Depending on how they’re set up, they might let 45% of sick people through, and yet 97% of the people they reject were not actually sick. Here’s a quick model to illustrate these numbers, and an illustration of the issue:

The thermometer can be adjusted to catch many more sick people, but that will be at the expense of healthy people. For example, if a thermometer has what’s called 90% sensitivity and 90% specificity, you might catch 90% of the people who have a fever, but you will also incorrectly classify 10% of those without fever as having one. If, say 0.1% of the people trying to get into a place are infected, it means that for each sick person you deny entrance, you will also deny the entrance of about 100 healthy people. And remember: 50% of infected are still going in because they just don’t have symptoms. That’s a total of 75% infected that the thermometers won’t catch.

It might still be worth it if it wasn’t reasonably expensive, since you need a person to operate the thermometer. If the operators also have other duties, such as referring people with fever to a testing site, or ensuring the enforcement of other measures such as masks, it is likely worthwhile. But otherwise, it’s an expensive way to filter only a quarter of people who’re infected. Better than nothing, not perfect.

Much better — and more expensive — thermometers might change the math. For example, thermal infrared cameras can spot people who seem to have fever, and then they are taken aside and their temperature is taken with a contact thermometer, which is much more reliable. With that, there might be fewer false positives. But other than that, it’s not clear that this measure is the best bang for your buck.

Thanks to Matt Bell for leading the research in this section.

Conclusion

There are things that can be done by citizens, businesses and governments to have a massive impact in reducing the transmission rate of the coronavirus. Everybody should be doing them:

- Wear home-made masks.

- Wash hands.

- Avoid spending a long time close to people who are speaking or singing.

- Avoid parties and other social gatherings, especially if they are with people from other social groups.

- Keep your distance from people. At the very least 2 meters. Ideally more. Don’t sit in front of people.

- Change the environment of your business to make it much harder for people to interact with each other.

In the next installment, we will go into the four measures that governments can apply relatively cheaply but that can have a tremendous impact in reducing the transmission rate: testing, contact tracing, isolations and quarantines.

If you want to receive the next installments of the article, sign up for the newsletter.

If you want to translate this article, do it on a Medium post and leave me a private note here with your link.

Translations

Spanish

Portuguese (alternative)

German

Italian

Vietnamese

Bahasa Malaysia

Thai

Japanese

Russian

Bulgarian (outside of Medium)

Macedonian

Serbian

Bosnian

Hebrew

This is Part 2 of our Article, Coronavirus: Learning How to Dance. In Part 3, we will look at the core of the measures every country needs to adopt: testing, contact tracing, isolations and quarantines. We will give specific recommendations on each, including a warning: Most countries are not approaching contact tracing right. If they continue their current path, they will end up like Singapore.

This has been a massive team effort with the help of dozens of people who have provided research, sources, arguments, feedback on wording, challenged my arguments and assumptions, and disagreed with me. Special thanks to Carl Juneau, Genevieve Gee, Matt Bell, Jorge Peñalva, Christina Mueller, Barthold Albrecht, the Masks4All team, Jeremy Howard, Elena Baillie, Pierre Djian, Yasemin Denari, Eric Ries, Shishir Mehrotra, Jeffrey Ladish, Claire Marshall, Donatus Albrecht, and many more. This would have been impossible without all of you.

Post a Comment